The Kinloch Players was the last example of a tradition that had existed in Scotland since Victorian times. There were similar companies in England and probably Wales and Ireland at that time. The Kinloch Players ran from 1941-1957. Other sources give different, incorrect dates. The company toured from Torphichen to Tain.

The Kinloch Players was the last example of a tradition that had existed in Scotland since Victorian times. There were similar companies in England and probably Wales and Ireland at that time. The Kinloch Players ran from 1941-1957. Other sources give different, incorrect dates. The company toured from Torphichen to Tain.

Fit-ups carried everything they needed for the presentation of their shows. There were baskets (hampers) of costumes and props, together with the actual ‘fit-up’.

Fit-ups carried everything they needed for the presentation of their shows. There were baskets (hampers) of costumes and props, together with the actual ‘fit-up’.

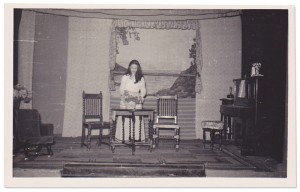

Town and village halls had a fixed stage or platform. This varied in size in every hall. The available height also varied. This meant that a sort of adjustable Meccano-like fit-up was needed for the scenery and lighting.

Members of the company learned their ‘parts’ whenever they had a few free moments. Unlike rep, where a show didn’t recur during a season, with a touring company, the same plays reappeared at every new date. This was useful as long as you hadn’t forgotten your lines while trying to remember at least a dozen other parts in the meantime. Members of the cast were issued with odd, but traditional, scripts.

The aim of all these companies was to make a living. There were no artistic pretensions. No desire to educate the public. If ‘Maria Marten or the Murder in the Red Barn’ put ‘bums on wooden benches’, that’s what they would play. If a Scottish subject like ‘Jeannie Deans or The Heart of Midlothian’ was presented it was because it filled the house, not because it had good literary credentials. Fit-ups had never heard of worthy bodies keen to improve the minds of the audience. As far as they were concerned the world didn’t owe them a living. They just got on with trying to earn one.

Ideally the Kinloch Players would consist of six to eight performers. Henry Parker and Mary Kinloch were part of the company throughout its lifetime. Henry Parker Junr. (who became Lawrence Parker and finally Larry Parker) was with the company on and off through the years. Others came and went. During the war, artistes were difficult to find. As the numbers varied, so the size of the cast affected the show. Cut versions were used. Artistes ‘doubled’. The company was managed by Henry Parker. Mary Kinloch looked after the finances and the wardrobe. During and after the war she also dealt with the Rationing. Artistes were not on ’shares’. Small but reliable salaries were paid. There was an interesting expression used for many years about pay-day ‘When does the ghost walk?’.

Ideally the Kinloch Players would consist of six to eight performers. Henry Parker and Mary Kinloch were part of the company throughout its lifetime. Henry Parker Junr. (who became Lawrence Parker and finally Larry Parker) was with the company on and off through the years. Others came and went. During the war, artistes were difficult to find. As the numbers varied, so the size of the cast affected the show. Cut versions were used. Artistes ‘doubled’. The company was managed by Henry Parker. Mary Kinloch looked after the finances and the wardrobe. During and after the war she also dealt with the Rationing. Artistes were not on ’shares’. Small but reliable salaries were paid. There was an interesting expression used for many years about pay-day ‘When does the ghost walk?’.

The company did not have any kind of subsidy. On the contrary, Entertainment Tax had to be paid on most tickets.

Very few production photographs ever existed of the Kinloch Players. From 1939, film stock was virtually unobtainable by individuals because of wartime restrictions. Professional photographers and studios received limited supplies. After the war, it took time for film to become available for use by the general public. ‘Front of house’ or publicity photographs were not used by the company. Classified ads. in local newspapers and day bills distributed to local shops and nailed to trees or small hoardings provided the company’s only publicity.

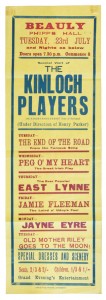

Programmes were not printed because casts changed and with six different plays a week it wasn’t a practical proposition. However, at various times simple duplicated ‘programmes’ with a brief description of the evening’s play were printed and numbered (price 2d each) and used as a raffle. They were ‘duplicated’ on a homemade machine using typed stencils and a hand-roller with a tube of ink. A printed programme was produced for the initial production of Jamie Fleeman with a cast and a list of scenes. It is the only existing programme of the Kinloch Players.

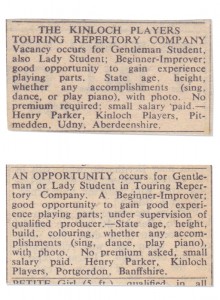

Most artistes were engaged when they answered an advertisement in the trade newspaper, ‘The Stage’. They received a standard letter telling them about the company, the experience they would gain and the salary they would be paid, usually around 30/- a week. Accommodation, often with full board would cost around 17/6 to £1, but they were not the usual theatrical digs.

Most artistes were engaged when they answered an advertisement in the trade newspaper, ‘The Stage’. They received a standard letter telling them about the company, the experience they would gain and the salary they would be paid, usually around 30/- a week. Accommodation, often with full board would cost around 17/6 to £1, but they were not the usual theatrical digs.

All period and character costumes were provided, but artistes were responsible for their own make-up (Leichner) usually bought from a branch of Boots. Stocks were held in most small towns for the local amateurs. There were no fares involved. The members of the company travelled on the back of a lorry, hired to move the company and all it’s equipment from one village or town to the next. It was a little self-contained community and as long as a newcomer learned the ground rules and observed the superstitions all would be well.

Earlier touring companies usually presented the play (as billed) followed by a comedy sketch to round off the evening. The Kinloch Players reversed the order and opened with a sketch and/or ‘turns’. Occasionally there would be a Go-as-you-please Competition.

Earlier touring companies usually presented the play (as billed) followed by a comedy sketch to round off the evening. The Kinloch Players reversed the order and opened with a sketch and/or ‘turns’. Occasionally there would be a Go-as-you-please Competition.

Henry Parker had a vent act and also did a club swinging ‘turn’. Henry Parker Junr. had a Chinese conjuring act billed as ‘Kai Yen Su’, sometimes with two female assistants. He also did paper tearing. Other artistes sang or danced. If the play was short, the evening was filled out with several items, combined into a kind of mini variety show. In the early years, for the mood music for the plays and the accompaniment of the ‘turns’ a piano provided the only music.

The sketches were traditional and performed in fit-ups through the years. Some were probably shortened versions of Victorian one-act plays. Others were adapted from vaudeville sketches. The West Highland Players had a sketch called ‘The mock doctor’, a very free version of ‘La malade imaginaire’. There were several one act straight plays including ‘The woman in Budapest’ and ‘A baby’s shoe’.

After the sketch or turns, Henry Parker or Mary Kinloch stepped through the ‘tabs’ and made a speech about the forthcoming productions. In rep theatres the custom was for the leading actor to step forward during the final curtain call, thank the audience for being there and announce the next production. By inserting it between the sketch and the play, Henry Parker made sure he had a captive audience for the forthcoming list of plays.

The main part of the evening’s entertainment followed.

The play was usually presented without an interval. The scenes or acts followed on with only a pause long enough to change the scenery and costumes. Unlike theatres, there were no bars waiting to take money from the customers for drinks or coffee.

The whole entertainment would usually last about an hour and three quarters. That was long enough when the seating consisted of wooden benches and plain chairs. At that time twice-nightly variety shows in theatres would last around one hour and forty or forty-five minutes. Cinema programmes were longer, with a first and second feature, news, trailers and sometimes ‘shorts’ (interest films or cartoons). Cinemas and theatres had padded tip-up seats.

For audiences, in rural areas, to have been willing to walk long distances, often in the dark and sit on wooden seats to watch the ‘Kinloch Players’ must seem very strange today. In 1950 the Scottish Press started to notice this strange phenomenon of a company of actors travelling to sometimes remote villages and managing to make a living at it.

But by 1955 making a living became harder. Henry Parker and Mary Kinloch were by then in their sixties and in spite of the enthusiasm of the young members of the company, keen to present a modern repertoire, the public became more theatrically sophisticated and less willing to leave the comfort of their homes for an evening’s entertainment.

But by 1955 making a living became harder. Henry Parker and Mary Kinloch were by then in their sixties and in spite of the enthusiasm of the young members of the company, keen to present a modern repertoire, the public became more theatrically sophisticated and less willing to leave the comfort of their homes for an evening’s entertainment.

The closing of the Kinloch Players in 1957 marked the end of the traditional touring fit-up in Scotland.